Jorge Zárate , 31 August 2025

Introduction

Airline economics has always stood at the intersection of industrial organization, public policy, and consumer behavior. Unlike many other industries, airlines operate in an environment where costs are highly fixed, demand is highly variable, and competition is tightly intertwined with government regulation and international politics. This makes aviation both a business and a public utility, subject to rules, subsidies, and geopolitical influences that do not apply with the same intensity to other sectors. In 2025, the complexity of the industry has only intensified.

On the one hand, demand for air travel remains robust, with global traffic reaching new records in 2024 and maintaining positive growth into 2025 (IATA, 2025). At the same time, the sector faces unprecedented constraints: aircraft production delays, engine reliability issues, sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) mandates, and heightened geopolitical uncertainty in key corridors such as Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Meanwhile, the rise of digital retailing and IATA’s New Distribution Capability (NDC) is reshaping how airlines interact with passengers and intermediaries, shifting bargaining power away from global distribution systems and toward airlines themselves.

The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive economic analysis of the airline industry in 2025 by revisiting classical concepts such as demand elasticity, yield management, and cross-subsidization, while integrating current issues such as NDC distribution strategies, sustainability mandates, and geopolitical constraints. To clarify these issues, mathematical reasoning is introduced where necessary, grounding the discussion in economic principles rather than anecdotes. The goal is to demonstrate that beneath the headlines, the logic of airline economics continues to explain why airlines price as they do, how they allocate scarce capacity, and what strategic options they will pursue in a volatile world.

Demand Elasticities and Mathematical Reasoning

Passenger demand in aviation has always been distinguished by its dual nature: a mixture of price-sensitive leisure travelers and time-sensitive business travelers. This heterogeneity is not incidental; it is central to the way airlines structure their pricing strategies. Economic analysis captures this through elasticity formulas. Price elasticity of demand (Ep) is calculated as the percentage change in quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in price. In leisure markets, Ep is typically greater than 1 in absolute value, indicating elastic demand, while in business markets Ep is less than 1, signaling inelastic demand (O’Connor, 2001).

Ep = %ΔQ / %ΔP

The implications of these values are profound. For leisure travelers, a 10% decrease in fares might lead to a 20% increase in bookings, while for business travelers the same fare cut might generate only a 5% increase. This divergence justifies differentiated fare structures and underlines why uniform pricing is economically irrational in air transport. Airlines would either price themselves out of the leisure market by charging too high a fare or leave money on the table by undercharging business travelers with inelastic demand.

Another key concept is the tapering of fares with distance. Long-haul fares typically exhibit lower costs per mile compared to short-haul services. Part of this reflects fixed costs spread over longer distances, but elasticity also plays a role: demand for long-haul markets is less sensitive to price increases on a per-mile basis, allowing airlines to price more competitively while still sustaining profitability (O’Connor, 2001). These mathematical insights are more than academic; they explain the basic pricing logic that continues to govern airline networks in 2025.

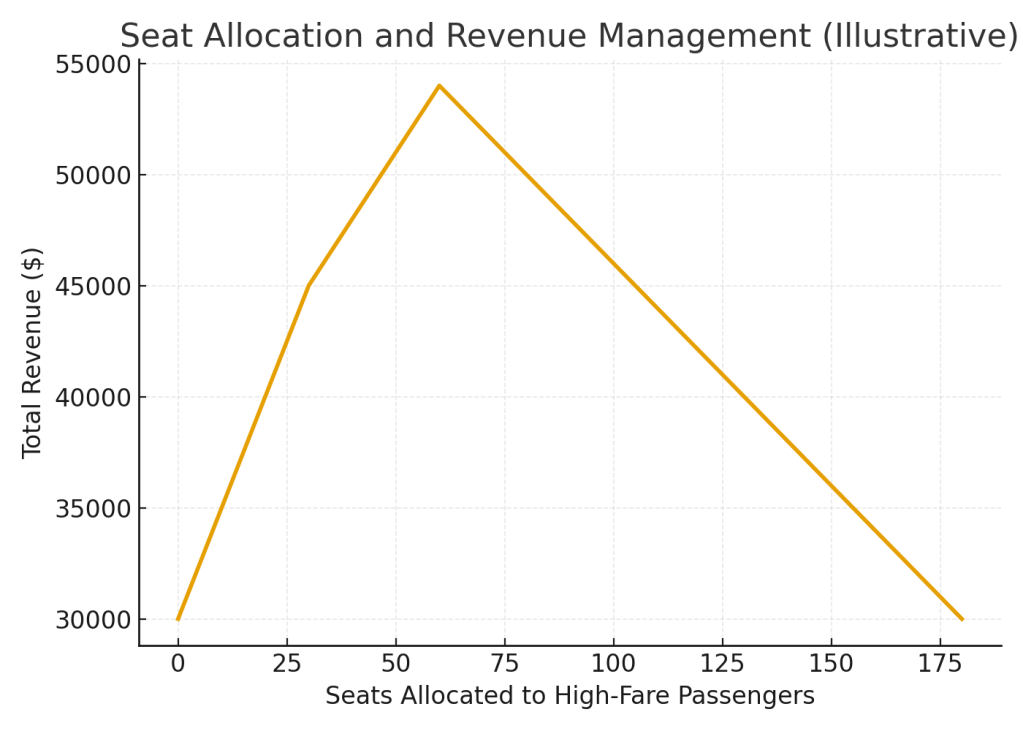

Revenue Management: Yield, Capacity Controls, and Segmentation

The core of airline economics in the post-deregulation era is revenue management, sometimes referred to as yield management. Yield itself is defined as the revenue earned per revenue passenger-mile (RPM), a simple ratio that masks the complexity behind its calculation. The real challenge for airlines is not simply to fill seats but to ensure that each seat is sold at the optimal fare class so that total revenue is maximized.

Yield is defined as:

Yield = Total Revenue ÷ Revenue Passenger-Miles (RPMs)

To achieve this, airlines employ a suite of techniques including overbooking, capacity-controlled discount fares, peak-load pricing, and dynamic inventory allocation. The optimization problem can be expressed mathematically as:

Max Σ (pi × qi), subject to Σ qi ≤ Q

where pi is the fare, qi is the number of tickets sold at that fare, and Q is aircraft capacity.

This is the foundation of yield management: overbooking, dynamic pricing, and controlling how many seats are sold at each fare level. In 2025, with constrained capacity, these techniques are more crucial than ever.

This reliance on yield management explains why consumers often encounter large price differences for the same seat depending on when and how they book. Far from being arbitrary, these differences are grounded in models of consumer behavior and optimization under constraints. What appears as pricing opacity is in fact a systematic application of microeconomic principles tailored to the realities of air transport.

Ancillary Revenues: Expanding the Revenue Base

A defining characteristic of the modern airline business is the expansion of ancillary revenues, which IATA estimates will reach $144 billion in 2025 (IATA, 2025). Ancillary revenues include baggage fees, seat upgrades, onboard sales, and bundled offers. While critics often dismiss these as “hidden fees,” they are in fact the logical extension of yield management. By unbundling services and charging separately for them, airlines can better segment willingness to pay among different passenger types.

From an economic perspective, ancillary revenues represent a method of consumer surplus extraction. Traditional fare models left value uncaptured because a one-size-fits-all ticket did not account for the varying preferences of travelers. By offering differentiated services at multiple price points, airlines maximize revenue per passenger rather than per seat alone. In 2025, this diversification provides resilience against fluctuating base fares and strengthens overall financial stability.

NDC Distribution: Reshaping Market Access

Perhaps the most important distribution development in recent years is IATA’s New Distribution Capability (NDC). The legacy system of fare distribution relied on global distribution systems (GDS) and EDIFACT protocols, which restricted airlines to filing static fares and limited their ability to personalize offers. NDC, by contrast, uses XML-based APIs that allow airlines to display dynamic fares, bundles, and ancillaries directly to agents and consumers (IATA, 2024).

Economically, this shift alters the distribution cost structure and changes the bargaining power dynamics between airlines and intermediaries. Airlines save on GDS fees, gain greater control over their product presentation, and can personalize offers based on customer profiles. NDC also enables airlines to transition from pure seat inventory management to total offer optimization, a shift that mirrors broader trends in digital retailing.

In 2025, the carriers that have embraced NDC are better positioned to capture incremental revenue and protect yields in a supply-constrained environment. Conversely, those that lag in implementation risk commoditization, as their products continue to be displayed in generic formats that limit differentiation.

Cargo: Mathematical and Strategic Considerations

Cargo remains an essential but often overlooked component of airline economics. While passenger services dominate revenues, cargo provides both diversification and resilience. In 2025, air cargo demand has grown significantly due to supply chain disruptions in ocean shipping and the expansion of e-commerce logistics.

The economics of cargo, however, are constrained by structural issues. The cube-out problem occurs when volume rather than weight limits the load factor. Airlines account for this using dimensional weight pricing:

Chargeable Weight = max(Actual Weight, Volume ÷ Dimensional Factor)

This pricing model ensures that shippers of low-density goods pay rates aligned with the economic use of space. Incentives for containerization and density optimization also reflect the principle of aligning customer behavior with airline cost structures (O’Connor, 2001). While cargo’s share of total airline revenues fluctuates, its strategic role as a stabilizer has been reinforced in 2025.

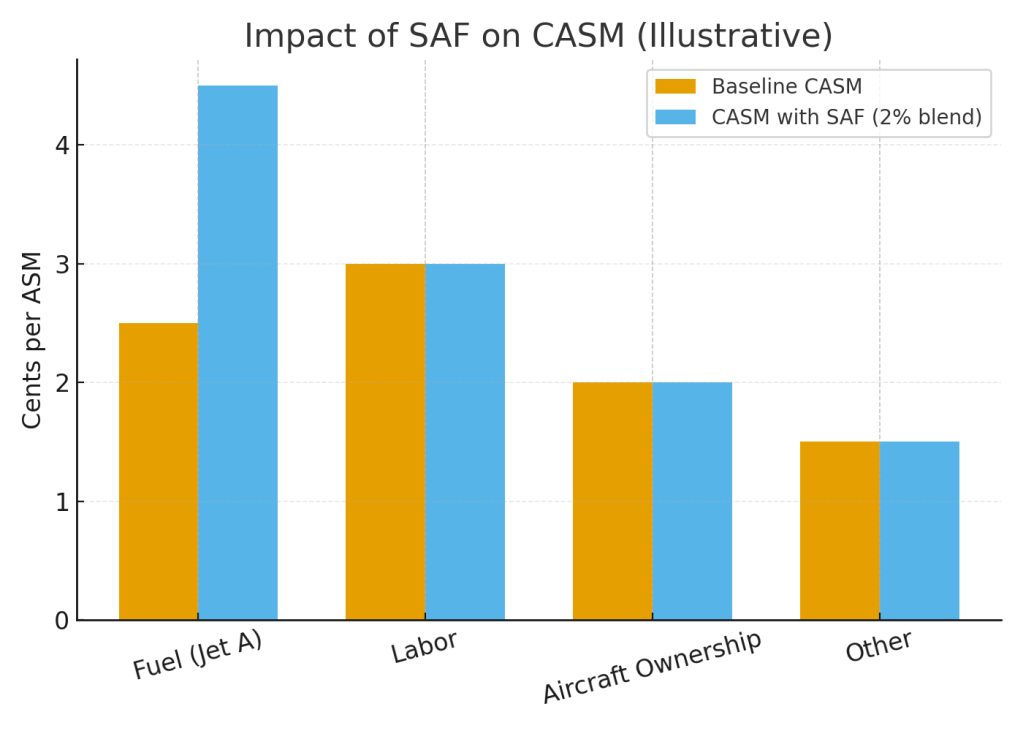

Sustainability as a Cost Function

Sustainability is no longer an optional public relations measure but a binding cost input. From January 2025, the European Union’s ReFuelEU Aviation mandate requires airlines to use a 2% blend of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), with higher requirements to follow (European Commission, 2023). Since SAF costs two to three times more than conventional jet fuel, this has a direct impact on the cost per available seat mile (CASM):

CASM = (Cfuel + Clabor + Caircraft + Cother) ÷ ASM

Airlines face a strategic choice: absorb the cost, pass it through to consumers, or lock in long-term SAF contracts to mitigate volatility. The differential pace of SAF adoption across regions also creates competitive disparities, with carriers based in SAF-rich jurisdictions better positioned to meet both regulatory and corporate customer requirements.

Geopolitical Constraints

The geopolitical context continues to exert a powerful influence on airline economics. The closure of Russian airspace since 2022 forces many Western carriers to reroute, increasing flight times, fuel consumption, and crew costs. Instability in the Middle East has further complicated traffic flows and reduced connectivity, while trade disputes introduce tariffs that raise the cost of aircraft, parts, and maintenance.

These are not temporary shocks but permanent structural variables in airline planning. Airlines now routinely incorporate geopolitical risk into their network optimization models, alongside demand forecasts and fuel prices. In 2025, geopolitics is as much a determinant of airline economics as traditional supply and demand dynamics.

Profitability and Outlook

Despite these constraints, the industry remains profitable. IATA projects net profits of approximately $36 billion in 2025, reflecting disciplined capacity management, robust ancillary revenues, and strong demand (IATA, 2025). This profitability is not a short-term anomaly but the outcome of airlines systematically applying economic principles: elasticity-based pricing, yield management, distribution control, and diversified revenue streams.

Conclusion: Strategic Outlook

The analysis of airline economics in 2025 reveals that the principles articulated decades ago remain essential for understanding the industry today. Airlines succeed not by chasing growth at all costs but by optimizing under constraints—allocating limited capacity efficiently, differentiating fares by elasticity, and leveraging ancillary and cargo revenues to stabilize income. NDC distribution represents a technological leap that aligns with these economic imperatives, while sustainability mandates and geopolitical realities reshape the cost and competitive environment.

Looking forward, the most successful carriers will be those that treat economic fundamentals, regulatory constraints, and technological innovations as integrated components of strategy. Growth will increasingly be defined not by raw expansion but by disciplined optimization, careful segmentation, and adaptive planning in a volatile geopolitical world.

References

- European Commission. (2023). ReFuelEU Aviation: Sustainable aviation fuels mandate. Brussels: European Commission.

- International Air Transport Association (IATA). (2024). NDC Implementation Guide. Geneva: IATA.

- International Air Transport Association (IATA). (2025). Economic performance of the airline industry: 2025 mid-year report. Geneva: IATA.

- O’Connor, W. E. (2001). An introduction to airline economics (6th ed.). Westport, CT: Praeger.